I get a lot of enquiries for architectural internships. Many students are either confused or highly opinionated on the kind of internships they need. So this note is for them. Partly, this also applies to other design fields such as software design, product design and so on — in any situation where there is “architecting” going on.

To become a good architect one need to be good at using both sides of the brain. An architect needs to grapple both with empirical knowledge as well as abstractions. Our field is very unusual in this requirement: most fields can work by gravitating towards one or the other but usually not both.

Those interested in pure sciences and maths for example need to worry only about rational thinking using abstractions. They do not really need much of empirical knowledge. They can introspect and work out internal contradictions in their theories and get productive work done; with no real connection to the outside empirical world. That is how Andrew Wiles sat through for over seven years working practically in secrecy to prove the much talked about Fermat's last theorem. Simon Singh wrote a fascinating book about it. http://simonsingh.net/books/fermats-last-theorem/who-is-andrew-wiles/ The advantage of abstract rational thinking is that knowledge can be quickly built up because an internal abstract framework is usually available on which things can be pegged.

Then there are fields such as medicine where much of the knowledge is empirical. Doctors can become better and better as they get more and more experience; as they absorb more and more information from real world situations and stitch them up using empirical, heuristic techniques in their mind. Of course, the process of building empirical knowledge is fraught with danger. I know of several doctors who have remained stupid and cannot really stitch up empirical knowledge -- even when they get experience.

It is not fully their fault: Building up of empirical knowledge is not amenable to an internal structure on which the knowledge can be built. A swallow does not make a summer, so making patterns out of experience requires a lot of humanity and depth which some people lack; especially those who cannot look beyond their work into other aspects of life. Also, if a doctor does not really encounter a difficult case, he would remain ignorant of the salient aspects of the case for years. I will again come to this point later on when I discuss empirical knowledge in architecture

To reiterate: Architects need to do both kind of thinking. We need to have abstractions. After all, no such project existed when an architect is given a plot to design. The architect is forced to conjure up one. The architect then has go all the way to empirical knowledge too. Such as, select the appropriate brick-bond for the external wall to reduce leakage, etc; which requires practical experience in that area. A discerning, sensitive architect would be considered quite mad by those around him or her -- because s/he would be dancing around in many areas in his head. In the initial years the thoughts of such architects tend to overwhelm the audience with the areas of concern: there are just too many an architect is sensitized to.

Young architects getting hitched to non-architects need to take care. A newly wed architect can easily bore his non-architect mate as he gets into lot of details which his mate may regard as unnecessary. The famous architect, Mies Van Der Rohe had said “God is in the details” and many architects understand that just too well. They happily get into details where others fear to tread; and in the process, lose the audience.

So now the question of internships: In any architect's life, an internship is very crucial — because that is the time the empirical side of the architects brain start getting inputs and gets built up. As noted before, building empirical knowledge is quite tough. There is no pre-existing framework. It is easy to misunderstand reality as one can easily keep working on some part of the real world while ignoring more important parts. Nicholas Taleb captured part of this issue in his books “Fooled by randomness” and “Black Swan” — though in those books the subject was not architecture or design.

It is possible to be misled when choosing the office where a student can do an internship. Some architects “pre-select” the area of the work they want to be involved in. Some professional architect's eye may be on a coffee table magazine or some award; and therefore may never get into those areas of practice which are really difficult and messy. I would never work with such architects or recommend them for internships.

One of the saddest aspect of architecture is that those who really need architects cannot afford them, and those who can afford architects can easily design and construct their built-environments without the help of any architect: The rich can easily build, demolish, and re-build till they get their environment right. So many architects unfortunately are working on the wrong problem — the real problems out in the world are not really the ones that many practising architects end up solving. It is not that cute little farm house which won an award. It is not the high end interior for a corporate office. It is often not even an office building that is now internationally recognised. Architects nibble at some 1% of the real design problems in the world.

So, the young architectural student out on an internship need to understand the challenges worth fighting for. Learn to ask the hard questions early in life. As empirical knowledge does not have a framework, the only substitute is to get deeply involved in many aspects of life: art, culture, ethics, philosophy, economics, psychology, sociology and so on. The only real way to build up empirical knowledge is to get exposed to as many facets of life as possible. Here is a nice article which explains why it is important to go after the right "pain" in one's life: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-manson/the-most-important-question_b_4269161.html

Pick a small to medium size architectural practice where the architects are deeply involved in a lot of such questions concerning life — not just the architecture being designed at that point in time. If one or more architects in that office have done some theoretical work or teaching, then the chances are that could be a good office to work for. If I was to do an internship, I would shy away from “brand” architects as most likely I would only sit in one corner doing some minor modification of some drawing that nobody is interested in.

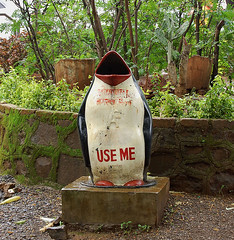

Internship should be a “two-way” process. Unfortunately, many students get into a pre-school “learning” mode with their mouths open like silly plastic penguins one finds all over India which is a lame substitute for dust-bins, often with the words “use me” painted on them. Yes, such students would get used and only rubbish would be placed into their mouths. A good intern should try to be in a position of influence (or at least gravitate towards that) where he or she has the freedom to exchange knowledge and indulge in healthy debates of life in that office. Obviously those debates must be based on sound background knowledge; and not just emotionally charged opinions.

If you want a quick summary: Internship in offices with noisy, healthy debates are the ones I would recommend.

This note also applies to fields such as software design; which is traditionally not regarded as “architecture” I have seen far too many silly software and websites that end up solving some non-essential part of life. There too, the designer has not got a proper grip on the empirical world around him/her.

All the best. May all architecture students bloom to become wonderful architects working on real problems

To become a good architect one need to be good at using both sides of the brain. An architect needs to grapple both with empirical knowledge as well as abstractions. Our field is very unusual in this requirement: most fields can work by gravitating towards one or the other but usually not both.

Those interested in pure sciences and maths for example need to worry only about rational thinking using abstractions. They do not really need much of empirical knowledge. They can introspect and work out internal contradictions in their theories and get productive work done; with no real connection to the outside empirical world. That is how Andrew Wiles sat through for over seven years working practically in secrecy to prove the much talked about Fermat's last theorem. Simon Singh wrote a fascinating book about it. http://simonsingh.net/books/fermats-last-theorem/who-is-andrew-wiles/ The advantage of abstract rational thinking is that knowledge can be quickly built up because an internal abstract framework is usually available on which things can be pegged.

Then there are fields such as medicine where much of the knowledge is empirical. Doctors can become better and better as they get more and more experience; as they absorb more and more information from real world situations and stitch them up using empirical, heuristic techniques in their mind. Of course, the process of building empirical knowledge is fraught with danger. I know of several doctors who have remained stupid and cannot really stitch up empirical knowledge -- even when they get experience.

It is not fully their fault: Building up of empirical knowledge is not amenable to an internal structure on which the knowledge can be built. A swallow does not make a summer, so making patterns out of experience requires a lot of humanity and depth which some people lack; especially those who cannot look beyond their work into other aspects of life. Also, if a doctor does not really encounter a difficult case, he would remain ignorant of the salient aspects of the case for years. I will again come to this point later on when I discuss empirical knowledge in architecture

To reiterate: Architects need to do both kind of thinking. We need to have abstractions. After all, no such project existed when an architect is given a plot to design. The architect is forced to conjure up one. The architect then has go all the way to empirical knowledge too. Such as, select the appropriate brick-bond for the external wall to reduce leakage, etc; which requires practical experience in that area. A discerning, sensitive architect would be considered quite mad by those around him or her -- because s/he would be dancing around in many areas in his head. In the initial years the thoughts of such architects tend to overwhelm the audience with the areas of concern: there are just too many an architect is sensitized to.

Young architects getting hitched to non-architects need to take care. A newly wed architect can easily bore his non-architect mate as he gets into lot of details which his mate may regard as unnecessary. The famous architect, Mies Van Der Rohe had said “God is in the details” and many architects understand that just too well. They happily get into details where others fear to tread; and in the process, lose the audience.

So now the question of internships: In any architect's life, an internship is very crucial — because that is the time the empirical side of the architects brain start getting inputs and gets built up. As noted before, building empirical knowledge is quite tough. There is no pre-existing framework. It is easy to misunderstand reality as one can easily keep working on some part of the real world while ignoring more important parts. Nicholas Taleb captured part of this issue in his books “Fooled by randomness” and “Black Swan” — though in those books the subject was not architecture or design.

It is possible to be misled when choosing the office where a student can do an internship. Some architects “pre-select” the area of the work they want to be involved in. Some professional architect's eye may be on a coffee table magazine or some award; and therefore may never get into those areas of practice which are really difficult and messy. I would never work with such architects or recommend them for internships.

One of the saddest aspect of architecture is that those who really need architects cannot afford them, and those who can afford architects can easily design and construct their built-environments without the help of any architect: The rich can easily build, demolish, and re-build till they get their environment right. So many architects unfortunately are working on the wrong problem — the real problems out in the world are not really the ones that many practising architects end up solving. It is not that cute little farm house which won an award. It is not the high end interior for a corporate office. It is often not even an office building that is now internationally recognised. Architects nibble at some 1% of the real design problems in the world.

So, the young architectural student out on an internship need to understand the challenges worth fighting for. Learn to ask the hard questions early in life. As empirical knowledge does not have a framework, the only substitute is to get deeply involved in many aspects of life: art, culture, ethics, philosophy, economics, psychology, sociology and so on. The only real way to build up empirical knowledge is to get exposed to as many facets of life as possible. Here is a nice article which explains why it is important to go after the right "pain" in one's life: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-manson/the-most-important-question_b_4269161.html

Pick a small to medium size architectural practice where the architects are deeply involved in a lot of such questions concerning life — not just the architecture being designed at that point in time. If one or more architects in that office have done some theoretical work or teaching, then the chances are that could be a good office to work for. If I was to do an internship, I would shy away from “brand” architects as most likely I would only sit in one corner doing some minor modification of some drawing that nobody is interested in.

Internship should be a “two-way” process. Unfortunately, many students get into a pre-school “learning” mode with their mouths open like silly plastic penguins one finds all over India which is a lame substitute for dust-bins, often with the words “use me” painted on them. Yes, such students would get used and only rubbish would be placed into their mouths. A good intern should try to be in a position of influence (or at least gravitate towards that) where he or she has the freedom to exchange knowledge and indulge in healthy debates of life in that office. Obviously those debates must be based on sound background knowledge; and not just emotionally charged opinions.

If you want a quick summary: Internship in offices with noisy, healthy debates are the ones I would recommend.

This note also applies to fields such as software design; which is traditionally not regarded as “architecture” I have seen far too many silly software and websites that end up solving some non-essential part of life. There too, the designer has not got a proper grip on the empirical world around him/her.

All the best. May all architecture students bloom to become wonderful architects working on real problems